When confronted with today’s controversy over religion and morality in the public square, conservative evangelicals often argue that the Founding Fathers were God-fearing, Bible-believing Christians who saw the United States as a divinely ordained “shining city” in the New World. The Left counters that the most prominent founders were deists, and that the Constitution was a purely secular document, which, with the addition of the First Amendment, erected a high wall of separation between church and state.

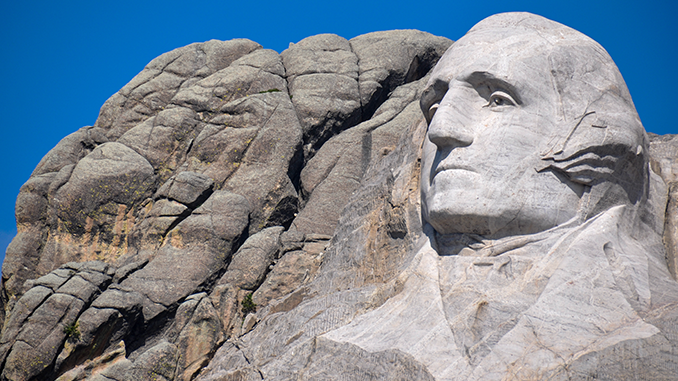

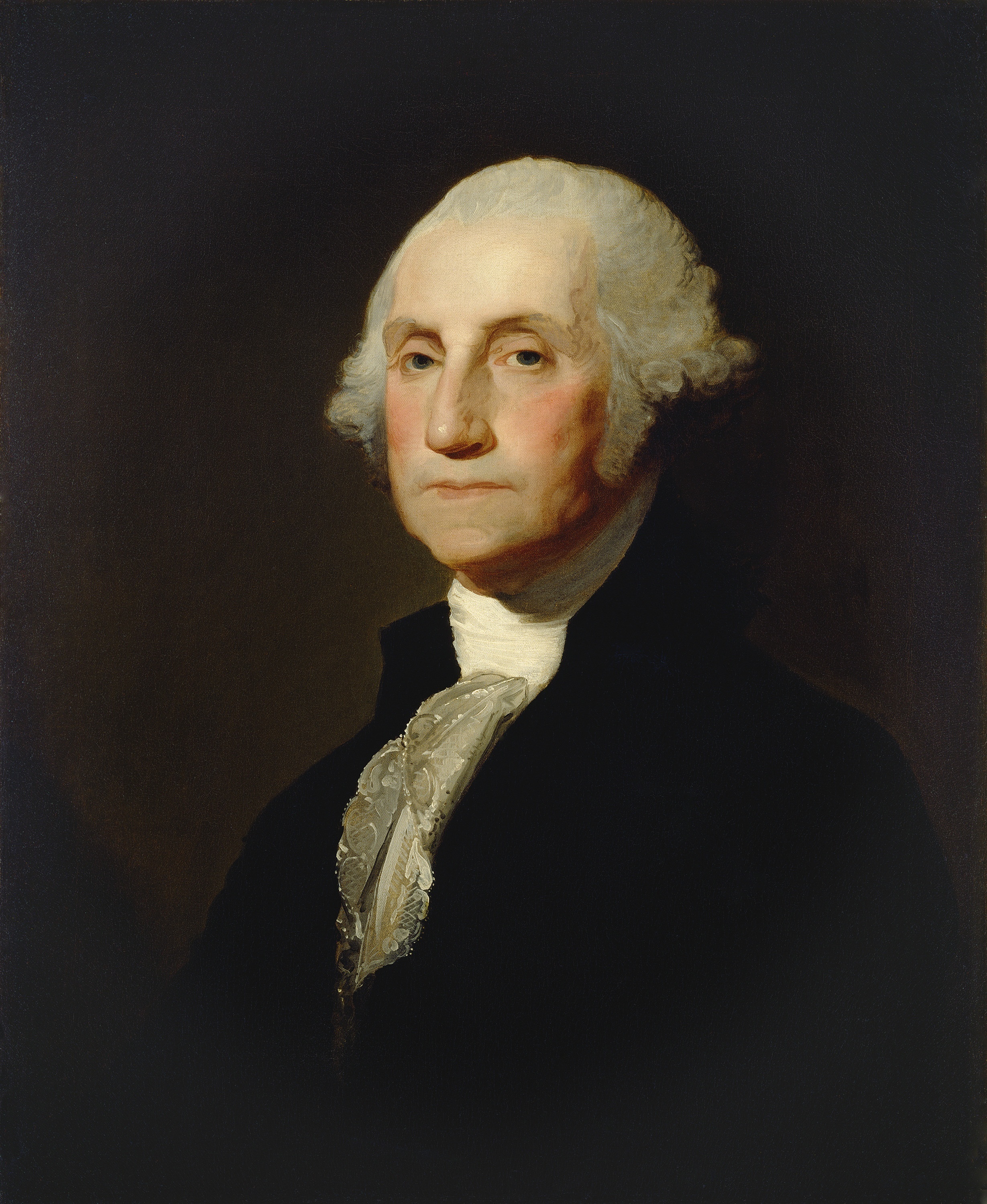

In the midst of this culture war, no founder’s life and legacy is as bitterly contested as our nation’s revolutionary leader and first President, George Washington. He has been called everything from “indifferent to religion” to a deist to a “warm deist” (whatever that means) to a “lukewarm Episcopalian” and finally (most often by our side) a God-fearing, Bible-believing Christian. These characterizations, which have been part of a now 200-year debate over Washington’s religious faith, led biographer Richard Brookhiser to observe, “No aspect of his life has been more distorted than his religion … For two centuries, Washington has been a screen on which Americans have projected their religious wishes and aversions.”1

What was the true nature of George Washington’s religious faith? Was he, in actuality, a believer in Jesus Christ?

While no respectable historian has accused Washington of being an atheist (at least in recent years), a large number of mainstream scholars (perhaps even most of them) reduce Washington’s religious beliefs to be little more than a utilitarian submission to some mystical, abstract conception of “Providence” (a favorite word of Washington’s).

Pulitzer prize-winning author Joseph Ellis exemplifies this tendency, saying Washington was “never a deeply religious man, at least in the traditional Christian sense of the term.”2 Eilis’s argument that Washington was not a Christian in the “traditional sense of the term” raises a key point that must be covered in any examination of a person’s faith, whoever that person might be.

What does it mean to be a “Christian”?

In mainstream history, “Christian” is used to categorize all those people and nations either founded upon or heavily influenced by traditions, practices, or institutions dating back to Jesus Christ. It is in this very broad sense that Western Europe is often called “Christendom” and that the Crusades are defined as “Christian.” By this broad definition, one could easily make the claim that virtually all the Founding Fathers were Christians, since most of them attended church, read their Bibles, and carried out their lives within the framework of westernized Christian traditions. But this serves no purpose whatsoever for the Bible-believing follower of Jesus who understands the term “Christian” to be much more substantive and sacred than a social science category.

According to the Bible, one achieves eternal salvation by placing his or her faith and trust in Jesus Christ and calling on the name of the Lord to be saved (Romans l0:9-13; Ephesians 2:8-9). Such a person is then transformed by the Holy Spirit and his life will reflect this new identity – one dependent on the indwelling of the Spirit and the Lordship of Jesus Christ. So, while the social scientist or geographer will say that there are 2.3 billion “Christians” in the world today, the number of individuals who have truly placed their faith and trust in Jesus Christ is considerably fewer.

Did George Washington possess a genuine and personal faith in God, and did he embrace Jesus Christ as the divine atonement for his sins? We will examine Washington’s faith, as best we can, to determine if this was the case.

Faith in God

According to Ellis, George Washington saw God “as a distant, impersonal force, the presumed well-spring of what be called destiny or providence.”3

That Washington saw God as the “well-spring” of “providence” is not contested by this author. The evidence for that is overwhelming.4 But George Washington himself would have objected to any characterization of God as being “distant” or “impersonal.” In 1789, a reflective Washington wrote:

When I contemplate the interposition of Providence, as it was visibly manifested, in guiding us through the Revolution, in preparing us for the reception of a general government, and in conciliating the goodwill of the People of America towards one another after its adoption, I feel myself oppressed and almost overwhelmed with a sense of divine munificence.5

As a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses and later of both the First and Second Continental Congress, Washington supported resolutions for and participated in days of prayer and fasting. As the Commander-in-Chief during the war, he made clear his support for prayer and submission to God through the appointment of Army chaplains and ordering mandatory church attendance for the men under his command.6 As President, he signed the first official Thanksgiving Day Proclamation in U.S. government history, declaring it the”duty of all nations” to “acknowledge” and “obey” the “Supreme Being.”7

In his First Inaugural Address, he emphasized chis duty of acknowledgment and submission, saying:

No People can be bound to acknowledge and adore the invisible hand, which conducts the Affairs of men more than the People of the United States. Every step, by which they have advanced to the character of an independent nation, seems to have been distinguished by some token of providential agency.8

Washington did not see God as some abstract, detached entity to which we owed little more than symbolic or ceremonial acknowledgment. For Washington, God was real, active, and worthy of our worship and obedience.

Washington did not see God as some abstract, detached entity to which we owed little more than symbolic or ceremonial acknowledgment. For Washington, God was real, active, and worthy of our worship and obedience. Click To TweetWashington also understood humanity’s proper posture before God to be one of humility. Washington personalized this ethic at an early age, when he copied out his famous “Rules of Civility,” which included the following injunction in Rule #108: “When you speak of God, or His attributes, let it be seriously and with reverence.”9

For this reason, he never played politics with his faith. In fact, Washington worked hard to stay above the religious battles in his day. He spent his public life working for unity. As the late Henry Cabot Lodge, a Washington biographer and famous statesman in his own right, explained, the first President “was as far as possible from being sectarian, and there is not a word of his which shows anything but the most entire liberality and toleration. He made no parade of his religion, for in this as in other things he was perfectly simple and sincere.”10

This, however, did not stop Washington from expressing repeatedly his fervent wish that Americans would embrace God, worship God, and obey God. “The hand of Providence has been so conspicuous in [the American Revolution],” he wrote Declaration of Independence signer Thomas Nelson, “that he must be worse than an infidel that lacks faith, and more than wicked, that has not gratitude enough to acknowledge his obligations.”11

It is beyond dispute that George Washington practiced a sincere faith in God. To argue or imply otherwise flies in the face of established historical facts, not the least of which are the voluminous writings of Washington himself.

Faith in Jesus Christ

George Washington knew the tenets of the Christian faith, including the basic salvation gospel message of Jesus Christ. This much is certain from Washington’s lifelong, formal association with the Anglican (later Episcopal) church, the fact that he came of age during the Great Awakening, his friendship with numerous Christian ministers and thinkers, and his own writings.

George Washington never played politics with his faith. In face, Washington worked hard to stay above the religious battles in his day. He spent his public life working for unity. Click To TweetWashington was a voracious reader, and his library contained Bibles, a concordance to the Scriptures, and the Book of Common Prayer. Specific allusions to biblical references in his speeches and letters demonstrate chat he was well familiar with the King James Bible.

George Washington Parke Custis, the Washington’s grandson (and George Washington’s adopted son), records that his grandfather, while president, would “read to Mrs. Washington, in her chamber, a sermon, or some portion of the sacred writings” every Sunday evening.12

Washington’s choice to incorporate the Bible into his presidential inauguration is further evidence of how sacred he viewed the Scriptures. Washington took the oath on the Bible and kissed it afterward. Then, he added “so help me God ” to the words. None of this was called for in the Constitution, nor was there any precedent for swearing-in democratic executives that Washington was seeking to follow. Washington later beseeched God in his inaugural address (a practice likewise followed by all his successors) and immediately attended worship services after his swearing-in. It is hard to imagine his doing any of that if his faith were not genuine or important to him.

For much of his life, Washington was a vestryman in his local Anglican parish. While it has been correctly pointed out that holding such a position was common for ambitious southern men of property, records show Washington was quite active in the role and some of his writings reveal a degree of pride in his service. Also, Washington’s affiliation with the Anglican (or Episcopal) church continued well beyond his ambitious youth. In fact, church attendance was an integral part of his entire life.

Lodge wrote that our nation’s father was “brought up in the Protestant Episcopal Church, and to that church he always adhered; for its splendid liturgy and stately forms appealed to him and satisfied him.”13

According to conservative author Tim LaHaye, “were George Washington living today, he would freely identify with the Bible-believing branch of evangelical Christianity.”14 While LaHaye is primarily making a cultural and political point, it comes close to doing what Brookhiser cautions us against, namely projecting our own Christian views and practices onto Washington. That he would share some of the same values and opinions held by LaHaye and other modern evangelicals is almost certainly true. However, the father of our country practiced his religious faith within the “stately” and “liturgical” traditions of Anglicanism, and would as likely be uncomfortable with the casual, expressive and demonstrative nature of modern evangelical practice.

While Washington probably shouldn’t be called an “evangelical ” (at least not in the contemporary sense of the term), his 18th-century affiliation to the Anglican church is evidence that he was in accord with its basic creeds, including a recognition of Jesus Christ as the Son of God.

Of course, reading the Bible and attending church do not a saved Christian make. They are simply pieces of the puzzle, and unfortunately, lacking an emphatic and unequivocal declaration of faith in Jesus Christ in at least his public writings, we are left with somewhat of a puzzle.

Possibly the most troubling and mysterious puzzle piece is Washington’s refusal to take communion. Prior to the Revolution, the evidence is scant and contradictory as to Washington’s communion practice. However, it is beyond dispute that George Washington, from the time he became a major public figure until his death, never cook communion.15 Washington would retire early from Sunday services on Communion Sunday, and would then send the carriage back for his wife, Martha, who (by all accounts) was a regular communicant. This fueled speculation then, and ever since, that George Washington was not a true believer in Jesus Christ. Indeed, it does raise troubling questions concerning Washington’s Anglican faith, since his denomination took (and still takes) communion very seriously.

The late John E. Remsburg, an author, lecturer, and lifelong member of the American Secular Union, authored an 1899 pamphlet that challenged Washington’s Christian faith. Citing correspondence from the early 1800s between Washington’s former ministers and various inquirers of information on the first president’s faith, Remsberg contended not only that Washington routinely declined communion, but that he never publicly embraced the full tenets of biblical Christianity.16Remsberg’s basic facts are correct and his analysis is compelling. However, he cites primarily secondhand letters and his choices are selective. For instance, he quotes one of Washington’s former ministers as calling Washington a “Deist,” but ignores other Washington contemporaries who testified to the Founding Father’s strong Christian faith.

One example of testimony ignored or overlooked by Remsberg is a claim made by 19th-century Baptist evangelist John Allen Gano. A famous Restoration movement revivalist, Gano said that his grandfather, Revolutionary War Chaplain John Gano, baptized General Washington by immersion during America’s War for Independence.17 A painting that depicts this event hangs to this day in Gano Chapel at William Jewell College in Missouri. Since there is no direct documentary evidence to support Gano’s contention, this baptismal story may likely belong in the same category as Parson Weems’s cherry tree legend. However, Gano’s service as Washington’s personal chaplain is not contested, and thus there is some plausibility to the tale.

If the story is true, it might explain the timing of things. According to Nelly Custis-Lee (Washington’s step-granddaughter, who he raised as a daughter), her grandfather stopped raking communion during the Revolutionary War.18 An intriguing possibility is that Washington’s outlook on communion may have changed along with his view of baptism, both of which the Anglican church saw as sacramental. Washington may not have wished to quit the Episcopal church, out of respect for his wife and sensitivity to his high public station. Thus, his refusal to take communion may have been a silent testimony of his new, more biblically correct perspective on the practice.

This, of course, is speculation as there is no way to confirm the Gano legend. More likely is that Washington was crying to cast himself as an ecumenical man of unity, given his newfound status as a national leader. It is during the Revolutionary War that Washington began cultivating relationships with Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist, Quaker, Anglican, and Catholic men of the cloth. Perhaps he felt that taking communion in the Anglican church compromised his credibility as a unifying figure.

Washington’s refusal to rake communion, when juxtaposed with his reluctance to mention the name of Jesus Christ in his writings (public or private), is what makes Remsberg’s analysis (and, by extension, Ellis and other modern historians) so persuasive.

Possibly the most direct evidence of Washington’s personal faith in Jesus Christ comes from a prayer journal found at Mount Vernon in the late 19th century. This is what many conservative evangelicals, including Tim LaHaye, point to in responding to skeptics like Remsberg and Ellis. The prayers contained in the journal include phrases that echo the most ardent Christian of today. In one, the journal declares, “Increase my faith in the sweet promises of the gospel; give me repentance from dead works; pardon my wanderings, and direct my thoughts unto thyself, the God of my salvation.”19

In another passage, we find the words, “Unite us all in praising and glorifying thee in all our works begun, continued, and ended, when we shall come to make our last account before thee blessed Savior.” lt then closes with the Lord’s Prayer.20

If the prayer journal is authentic, it seems clear that George Washington embraced Jesus Christ as the Son of God and as his Savior, his apparent refusal to cake communion notwithstanding. However, the prayer journal is in dispute.

Ed Lengel, Associate Editor of the Papers of George Washington at the University of Virginia, says that the disputed journal “almost certainly is not authentic.” According to Lengel, it either belonged to “another member of his family” or it is a “forgery.”21

It is tempting for conservatives to dismiss Lengel’s commentary as “liberal bias,” but ultimately, the real blame for this mystery and controversy lies with Washington himself. The Father of our country had plenty of opportunities to categorically declare his Christian faith. If this disputed prayer journal remains the best evidence for his faith in Jesus Christ, surely Christians today must acknowledge this to be frustrating and disappointing.

Of the undisputed writings, the best evidence one can muster for a self-affirmation of Washington’s faith is the circular letter to the state governors following his resignation as Continental Army Commander-in-Chief. Though it is written in the handwriting of one of his aides and the reference to Jesus is mildly oblique, the 1783 letter is worth quoting:

I now make it my earnest prayer, that God would have you, and the State over which you preside, in his holy protection, that he would incline the hearts of the Citizens to cultivate a spirit of subordination and obedience to Government, to entertain a brotherly affection and love for one another, for their fellow citizens of the United States at large, and particularly for their brethren who have served in the Field, and finally, that he would most graciously be pleased to dispose us all, to do justice, to love mercy, and to demean ourselves with that charity, humility and pacific temper of mind, which were the characteristics of the Divine Author of our blessed Religion, and without an humble imitation of whose example in these things, we can never hope to be a happy Nation.22

A skeptic might argue that Washington was merely highlighting the beneficial nature of Jesus’ teachings and example, as Thomas Jefferson (a self-described Unitarian) routinely did. However, Washington (or an aide writing for Washington) very pointedly says “Divine Author,” which serves as fairly convincing evidence that Washington either personally embraced Jesus’ divinity or, at least, authorized a letter, under his signature, that affirmed Jesus’ divinity. Whatever Washington’s reasons for not taking communion or publicly proclaiming Jesus Christ in an unmistakable manner, Mrs. Custis-Lewis made it clear in a February 26, 1833, letter (one chat Remsberg and others fail to mention) that she saw her grandfather as a true believer in Jesus Christ:

I should have thought it the greatest heresy to doubt [my grandfather’s] firm belief in Christianity. His life, his writings, prove that he was a Christian. He was not one of those who act or pray, “that they may be seen of men.” He communed with his God in secret.23

This would, of course, be entirely consistent with his undisputed respect for the Bible and his membership in the Episcopal church as well as his reticence to hold up the depth and specifics of his faith for public examination.

A life reflecting a Christian testimony

Washington’s self-discipline and high moral character are the stuff of legend. It is not necessary for this article to prove that Washington was a moral man. However, can we see his moral character as a manifestation of his faith?

A clue that Washington’s morality was more than mere Stoicism is found in one of his famous “General Orders” issued at Valley Forge in 1778: “To the distinguished character of patriot, it should be our highest glory to laud the more distinguished character of Christian.”

It is clear that Washington associated proper conduct with Christian principles of morality. It is therefore not a stretch to conclude that Washington’s own moral compass was set according to the Christian teachings he had grown up on.

This is a good point, however, to turn our attention to another influence on Washington’s life and conduct that many Christians find particularly unsettling. George Washington was a Freemason, and a large number of Christians today categorize Freemasonry as, at best, a fraternal cult and, at worst, an insidious satanic force for evil.

This article cannot hope to examine the controversies surrounding Masonic membership and rituals. The basic facts are these: George Washington joined the Masonic order in 1752 (the same century that Freemasonry came to the New World in the first place) and soon advanced to “Master Mason.” According to the George Washington Memorial Masonic Temple in Alexandria, Virginia, Washington visited various Masonic lodges and participated in Masonic events throughout the remainder of his life. In 1788, he was named “charter Worshipful Master of Alexandria Lodge No. 22” and served as “Acting Grand Master” in 1793 when he laid the cornerstone for the new nation’s capital. His funeral included Masonic rites along with those of the Episcopal Church.24

It is clear that Washington associated proper conduct with Christian principles of morality. It is therefore not a stretch to conclude that Washington's own moral compass was set according to the Christian teachings he had grown up on. Click To TweetThere is no evidence that Washington willingly or knowingly subscribed to any satanic ritual or conspired to supplant American government with a “secret society” of some kind. In fact, he routinely warned against factions and “secret societies” throughout his life. Washington’s own words explain his affiliation with Freemasonry:

Being persuaded that a just application of the principles on which the Masonic Fraternity is founded must be promotive of private virtue and public prosperity, I shall always be happy to advance the interest of the Society and to be considered by them as a Brother.25

The other troubling aspect of Washington’s Christian testimony is that he owned slaves. Yet Washington’s own writings bear witness to the struggles of his conscience on this issue. As a colonial Virginia legislator, Washington worked to restrict slavery. By the time of the Revolution, he vowed never again co buy or sell a slave. In private correspondence, Washington condemned slavery repeatedly.26

In the 1780s and ’90s, he explored ways to free his slaves while keeping Mount Vernon solvent. His frustration in not being able to do so is seen in a 1794 letter to his secretary, in which he refers to his slaves as “a certain species of property I possess, very repugnantly to my own feelings, but which imperious necessity compels.”

Finally, in his last will and testament, Washington ordered freedom for all his slaves upon the death of his wife (Martha would free them before she died) and directed that his estate should help provide for them after their liberation.27 Interestingly enough, his conscientious struggles with slavery began about the time of the Revolutionary War. Could this have been a reason for declining communion? Again, we can only speculate.

How a person faces the prospect of death is another indicator of where one stands in relationship to his or her faith. According to Lodge, Washington “regarded death with entire calmness and even indifference” and was helped in this “by his religious faith.”28 According to family and friends, when death came in 1799, Washington made sure his final affairs were in order and that his wishes for funeral arrangements were to be honored. Once those assurances were given, he met his end with utter peace.

We cannot know for certain anyone’s heart other than our own, and sometimes even that is problematic. However, based on overwhelming evidence (and this article covers only a small part of that), it is beyond question that George Washington believed in God and was a man of reverential worship and prayer. The assessment of many historians that Washington was a deist, no matter how often it is repeated, is demonstrably false.

In his public rhetoric, Washington expressed his faith in general terms. Thus, there isn’t as much direct evidence concerning a personal faith in Jesus Christ, other than (if authentic) his prayer journal or a small number of indistinct references to Jesus or Christianity in other writings. This is certainly disappointing, and we must acknowledge the possibility that Washington may not have enthusiastically embraced a personal relationship with Jesus Christ.

Nevertheless, for those who hope to pass George Washington on the “streets of gold” one day, some measure of assurance can be found in the words of his granddaughter, Nelly Custis-Lee, who likened questioning Washington’s Christianity with doubting “his patriotism” and “his heroic, disinterested devotion to his country.”29

Whatever the specifics of Washington’s faith, it is clear he was prepared to meet his Maker, and he knew what the Christian faith said was necessary to do so on good terms. George Washington’s last words were “‘Tis well” – a peaceful sentiment that all true Christians can lay claim to when the curtain closes on their mortal life.

SUGGESTED READING

America’s God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln, by Mark A. Noll. Oxford University Press, 2002.

Founding Father: Rediscovering George Washington, by Richard Brookhiser. Simon & Schuster, 1996.

The Founders on Religion: A Book of Quotations, by James H. Hutson. Princeton University Press, ‘ 2005.

George Washington, by Henry Cabot Lodge. Cumberland House, original published 1898 (new edition 2004).

George Washington’s War: The Forging of a Revolutionary Leader and the American Presidency, by Bruce Chadwick, PhD. Sourcebooks, Inc., 2004.

God and the Oval Office: The Religious Faith of our 43 Presidents, by John C. McCollister, Ph.D, W Publishing Group, 2005.

His Excellency: George Washington, by Joseph Ellis. Knopf, 2004.

Martha Washington: An American Life, by Patricia Brady. Viking, 2005.

Prayers of our Presidents, by Jerry MacGregor and Marie Prys. Baker Books, 2004.

Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington by his Adopted Son, George Washington Parke Custis, by George Washington Parke Custis. Originally published by Derby & Jackson in 1860. Republished by American Foundation Publications, 1999.

WEBSITES OF INTEREST

Letter from Nelly Parke-Custis discussing Washington’s faith, found at Wallbuilders website

George Washington Masonic National Memorial

The Papers of George Washington

John Remsberg’s analysis of Washington’s Christianity

NOTES

1Richard Brookhiser. Founding Father: Rediscovering George Washington (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), p. 144.

2 Joseph J. Ellis. His Excellency: George Washington (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004), p. 151.

3 Ibid.

4 Since Washington sometimes referred to Providence as ‘She’ and ‘It’ (in addition to ‘ He”), ii would be a mistake to associate that term with God directly. For Washington, “Providence’ was more a manifestation of God’s superintending will.

5 James Hutson, ed. The Founders on Religion: A Book of Quotations (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), p. 180.

The quote is from a letter George Washington sent the Philadelphia Council, April 20, 1789.

6 Bruce Chadwick. George Washington’s War (Naperville: Sourcebooks, Inc. 2004), p. 111.

7 George Washington. Thanksgiving Proclamation, October 3, 1789. Papers of George Washington (online resource maintained and edited by University of Virginia and found at http://gwpapers.virginia. edu/)

8 James Hutson, ed. The Founders on Religion, p. 182.

9 George Washington, ed. Rules of Civility. These can be found in many books and on many sites on the Internet. There is an entire section dedicated to them at the University of Virginia Papers of George Washington, previously cited.

10 Henry Cabot Lodge. George Washington: The American Statesman Series (Nashville: Cumberland House Publishing, Inc., 2004). Original published in Boston by Houghton Mifflin, ca. 1898.

11 James Hutson, ed. The Founders on Religion. This quote is from a letter Washington sent Thomas Nelson, August 20, 1778.

12 George Washington Parke Custis. Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington, by his Adopted Son, George Washington Parke Custis (Bridgewater: American Foundation Publications, 1999), p. 508. This memoir was first published in 1860 by Derby & Jackson in New York.

13 Henry Cabot Lodge. George Washington.

14 Tim LaHaye. Faith of our Founding Fathers (Brentwood: Wolgemuth & Hyatt, 1987), p. 113.

15 Joseph Ellis, p. 45. The evidence for this is overwhelming, with some historians (such as Ellis) going so far as to say he “never’ took Communion (even in his youth).

16 John E. Remsberg. Six Historic Americans. The portion dealing with George Washington is excerpted and published online by www.infidels.org. The excerpt can be found at www.infidels. org/librarylhistorical/john_remsburglsix_historic_americans/chapter 3.html#2

17 The baptismal claim is contained in this online biography of Chaplain Gano. www.therestorationmovement.com/gano,john.htm

18 Custis-Lee, Nelly. Letter to Jared Sparks. February 26, 1833. This letter is published online by Wallbuilders at www.wallbuild- ers.com/resources/search/detail.php?Resource1D=13

19 Excerpts from the prayer journal are provided by Tim LaHaye in Faith of our Founding Fathers, PP· 110·113·

20 Ibid.

21 This quote is from an email exchange with Mr. Lengel.

22 George Washington. Circular Letter to the States, 1783. Papers of George Washington, previously cited.

23 Nelly Custis-Lee. Letter to Jared Sparks.

24 These facts, confirmed by varied sources, are all reported by the George Washington Masonic National Memorial at its website: www.gwmemorial.org/

25 This quote is published online by the George Washington Masonic National Memorial.

26 Evidence for this is overwhelming. Both Mount Vernon

(www.mountvernon.org) and the University of Virginia Papers of George Washington (http://gwpapers.virginia.edu/) provide articles and selected correspondence from Washington himself on this subject.

27 You can read the full text of Washington’s last will and testament at the University of Virginia Papers of George Washington .

28 Henry Cabot Lodge. George Washington, p. 490.

29 Nelly Custis-Lee. Letter to Jared Sparks, Previously cited.

This article originally appeared in The Baptist Preacher’s Journal, Volume 16, No. 1 (Summer 2006) and is authored by Brian Tubbs. Learn more about Brian by visiting his website by clicking here.

Very interesting and informative article on Washington’s faith in God. The author certainly did his homework. Thanks for publishing this article.